LDA

低密度アモルファス氷 / Low-density Amorphous Ice

“A random yet ordered ice.”

Mishima et al. have shown that there are two types of amorphous ice, and that a first-order phase transition has been observed between the two types of amorphous ice. (Mishima 1994) Of these, the low-density amorphous phase observed at low pressure is known to be energetically more stable and has less entropy (more ordered) than the high-density amorphous phase on the high pressure side. (Klug 1989)

The possibility of a first-order phase transition between two random phases has been investigated in various models in recent years, and recently experiments have begun to reveal a number of systems in which a liquid-liquid phase transition (other than water) occurs. (Kurita 2004) It is not surprising that water also undergoes a first-order phase transition between two random phases.

However, the occurrence of a first-order phase transition also means that phase coexistence occurs. (YMT2014) In other words, the two phases must expel each other, resulting in the formation of a phase interface between the two phases. Can we explain on a molecular scale how a substance with relatively short-range interactions, such as water, can form two structural domains and recognize and exclude each other’s domains?

This was my biggest question. For such phase separation to occur, both phases do not need to self-aggregate; if only one of the phases aggregates, the remaining phase is forced to form another domain. In the case of gas-liquid coexistence, the liquid phase is the self-cohesive phase and the gas, even though it is not cohesive, will result in the creation of a domain. In the case of the liquid-liquid phase transition of water, since the LDA phase is ordered, I thought that there must be a mechanism within the structure of the LDA that allows it to aggregate itself and become more stable than the other.

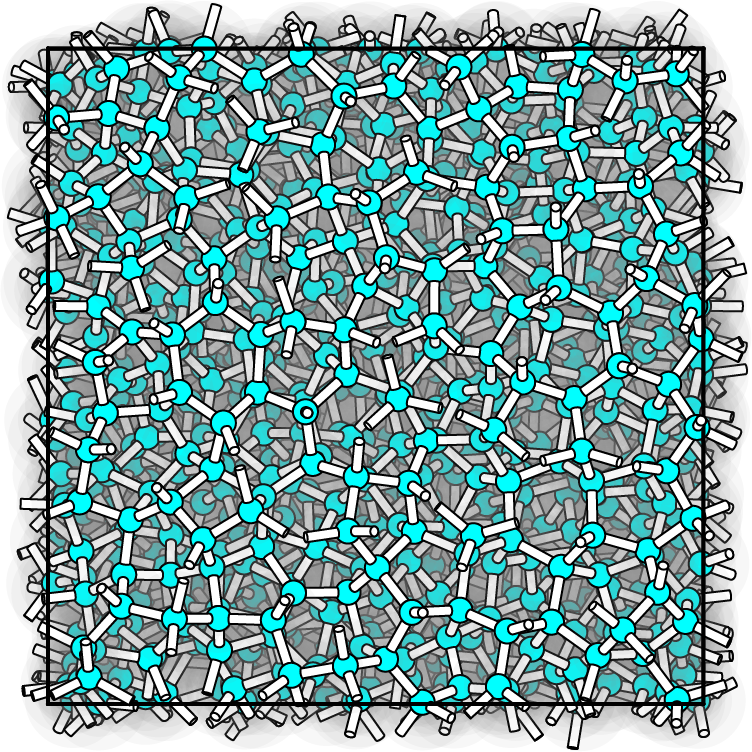

The most important structural feature of low-density amorphous ice is that all water molecules are nearly tetracoordinated. Although there have been many circumstantial evidences that supercooling of water leads to the progressive aggregation of tetracoordinated water molecules (Tanaka 1998), there has been no theory to properly explain how the preference for tetracoordination itself leads to self-aggregation. I believe that the introduction of the concept of vitrite can explain this self-aggregation property. (MBO2007)

三島らの研究により、アモルファス氷には2種類あることが知られており、しかも2つのアモルファス氷の間には一次相転移が観察されています。(Mishima 1994)このうち、低圧で観察される低密度アモルファス相は、高圧側の高密度アモルファス相よりも安定で、エントロピーも小さい(より秩序的)ことが知られています。(Klug 1989)

2つのランダム相の間で一次相転移が起こる可能性については、近年いろんなモデルで調べられ、また最近では実験でも(水以外で)液液相転移する系がいくつもみつかりはじめました。(Kurita 2004)水も2つのランダム相の間で一次相転移がおこっても不思議はないと考えられます。

ただし、一次相転移が起こるということは、相共存がおこるということでもあります。(YMT2014) つまり、2つの相が、互いを排斥しあい、結果として2つの相の間に相界面が形成される必要があります。水のような、比較的短距離な相互作用しかもたない物質が、2種類の構造ドメインを形成し、かつ互いのドメインを認識して排斥しあうという状況を分子スケールの描像で説明できるでしょうか?

これが私の最大の疑問でした。このような相分離がおこるためには、実は両方の相がそれぞれ自己凝集する必要はなく、どちらか片方の相だけが凝集すれば、残る相は自動的に排除されて別のドメインを作ります。気液共存の場合は、液体相が自己凝集性を持つ相であり、気体は凝集力がなくても、結果的にドメインを作ることになります。水の液液相転移の場合は、秩序があるのはLDA相なので、LDAの構造のなかに、自分たち同士が集まって、より安定になれる仕掛けがあるに違いない、と私は考えました。

低密度アモルファス氷の構造上の最大の特徴は、すべての水分子がほぼ4配位になっている点です。水を過冷却すると、4配位の水分子がどんどん凝集するという状況証拠は多数報告されてきましたが、(Tanaka 1998)4配位を好む性質自体が、自己凝集をもたらすことを、きちんと説明する理論はありませんでした。私は、ガラス状氷の構成部品(vitrite)という概念を導入することで、この自己凝集性を説明できると考えています。(MBO2007)

genice2 CRN1 -f svg[shadow] > CRN1.svg

Figure: Example of a hypothetical LDA structure. This structure is an artificially generated structure using the diamond structure as a starting point and may not be identical to a real LDA.

図: 仮想的なLDAの構造の例。この構造は、ダイヤモンド構造を出発点として、人工的に生成された構造であり、本物のLDAと同一ではないかもしれない。

References

- (Mishima 1994) アモルファス氷の一次相転移 O.Mishima, J. Chem. Phys. 100, 5910 (1994).

- (Klug 1989) 低密度アモルファス氷のエントロピー E. Whalley, D. D. Klug, and Y. P. Handa, Nature 342, 782 (1989).

- (Kurita 2004) 液液相転移 R. Kurita and H. Tanaka, Science 306, 845 (2004).

- (Tanaka 1998) H. Tanaka, Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 113 (1998).

Linked from

- 3Dプリンタ用データ

- 3Dプリンタ用データ

- LDA

- Network Motif of Water

- _computation

- vitrite

- まとめ

- アモルファス氷

- ネットワーク主体論

- ネットワーク物質のアモルファス構造解析

- 低密度アモルファス氷